by Andrea Tucci,

The handshake did not go unnoticed. On December 19, the presidents of Turkey and Iran exchanged warm greetings during a summit in Cairo, just ten days after Bashar al-Assad fled to Moscow. Assad, a strategic ally of Iran and a thorn in Turkey’s side, represented a critical focal point in the regional geopolitical landscape.

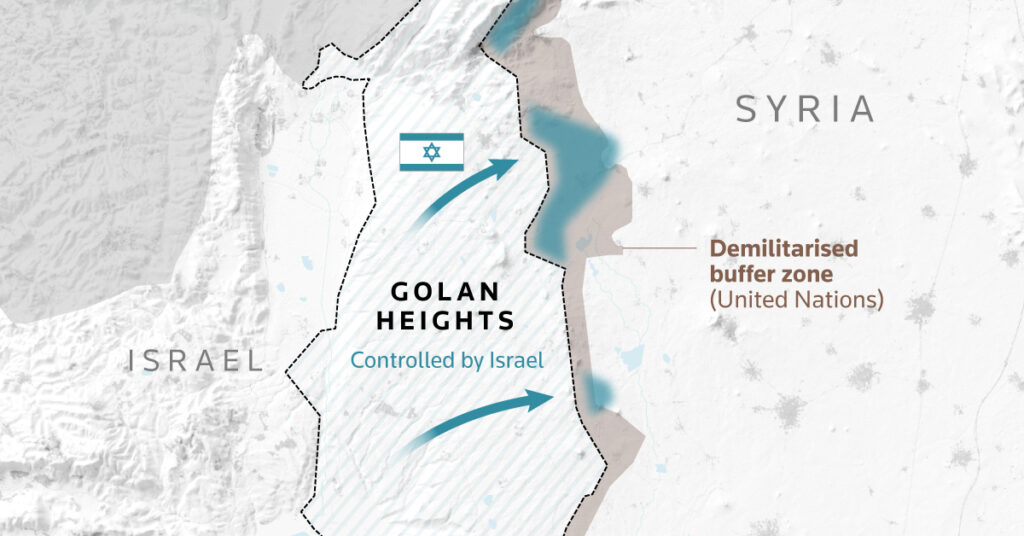

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a supporter of the rebels responsible for ousting the Syrian president, now plays a key role in shaping the future of his neighboring country. Meanwhile, another regional player watches closely. Shortly after Assad’s regime fell, Israel occupied the demilitarised buffer zone in the Golan Heights, launching incursions into Syrian territory and hundreds of strikes on military infrastructure. The stated objective: to prevent heavy weaponry and chemical arms from falling into the hands of terrorist groups, for instance

Photo: Map of the demilitarised buffer zone in the Golan Heights occupied by Israel

Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the leading Syrian opposition group, formed after successive splits with the Islamic State and al-Qaeda, has in the past expressed solidarity with Hamas. In a statement, Turkey’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemned Israel’s actions, stating: “At this delicate moment, when the Syrian people aspire to peace and stability, Israel once again demonstrates its occupation-driven mentality.”

Ankara aims to make Syria an example of regional stability and a tool for Turkey’s strategic influence. However, any developments in Syria that Israel perceives as a threat to its interests could spark new tensions between the two countries. According to many observers, Israel would have preferred a weak but predictable Assad, who had maintained a calm border since 1974, the year of the disengagement agreement signed with Hafez al-Assad.

Ahmad al-Sharaa, the leader of HTS, urged the international community to “act urgently” to ensure Syria’s sovereignty, emphasizing to Syria TV that the interim government’s priorities include meeting the population’s basic needs and building a more stable and just future.

While Tel Aviv intensifies its operations in the Golan Heights—partly to appease its far-right allies—Ankara continues its offensive against Kurdish forces in northeastern Syria, which it considers an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), designated as a terrorist organization. A fragile ceasefire mediated by the United States, following the Turkish-aligned factions’ capture of Tall Rifaat and Manbij, halted further advances to prevent the fall of the Kurdish-majority city of Kobani.

“Turkey focuses on Kurdish groups, while Israel aims to contain Iran,” analysts note. Both actors, however, share an interest in a politically stable Syria that would curb Tehran and Moscow’s influence.

Unlike Tehran, Turkey does not seek regional escalation and aims to integrate its allies into Syrian structures.Nonetheless, uncertainties remain regarding the positions of other regional players, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which oppose the Islamization of power in Damascus and could play a crucial role in post-war reconstruction.

Finally, the role of the United States remains to be seen. Washington could restrain Israeli ambitions in the Golan Heights and reduce its own involvement in Syria.

It remains to be seen whether Donald Trump’s administration, which may decide to disengage the 2.000 or so U.S. troops currently present in Syria, will want to get involved enough to avoid a clash between its main ally in the region, that is Israele and Turkey NATO’s partner.