by Adriano Izzo, Civil Lawyer and President of the Gennaro Santilli Foundation,

If Bella Baxter really existed and lived in our time, what social, cultural and legal obstacles would she encounter? Would she really be free to express herself, to discover the world, travel, meet people, have sex, love?

To answer this question we must first explain who Bella Baxter is.

Only after doing so – strictly without prejudice – can we try to understand what her fate would be in a society like ours.

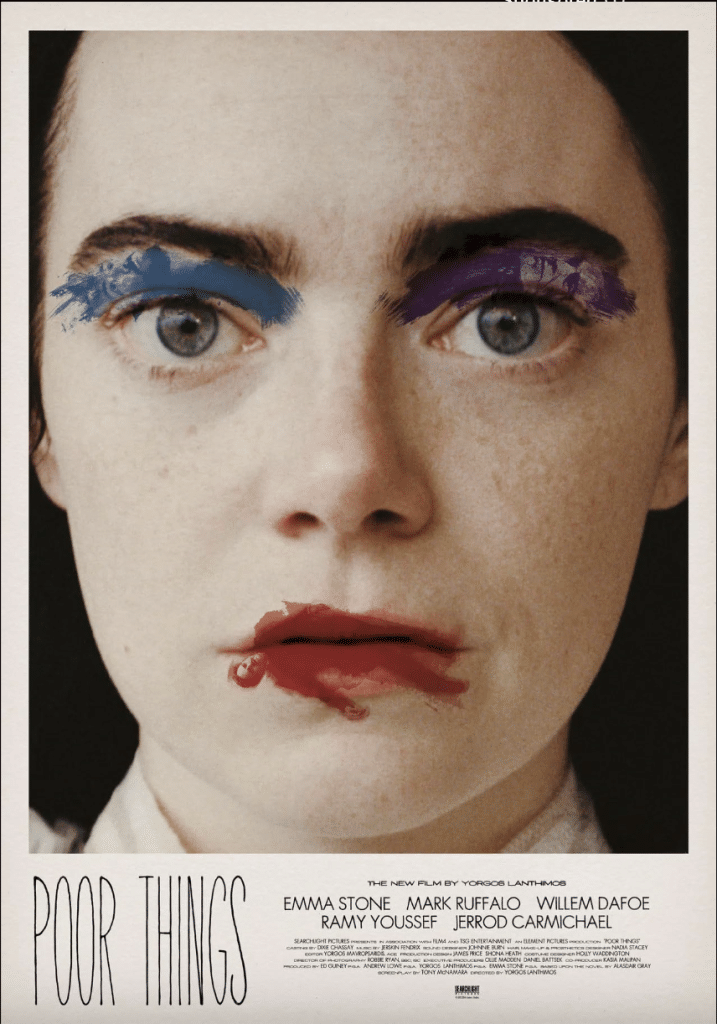

Bella Baxter is the protagonist of the highly acclaimed film by the provocative director Yorgos Lanthimos Poor Creatures! played by an exceptional Emma Stone (winner of the Oscar for best actress).

Based on the novel of the same name by the Scottish writer Alasdair Gray and inspired by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the film is an aesthetically perfect satire on the Victorian morality of the time (and, in general, on bigoted and prohibitionist thought), which finds in its protagonist the l the complete expression of a human being free from conditioning and hungry for knowledge, life, people, places.

Bella Baxter is a young woman who committed suicide in the Thames and is reborn thanks to the visionary genius of the surgeon Godwin Baxter – an amazing Willem Dafoe – who transplanted the brain of the child she was carrying in her womb into her skull.

The film follows the growth of Bella Baxter, a female Frankenstein with the cognitive abilities of a newborn baby who evolves, reaching an awareness of herself and her body which leads her, free and rebellious, to emancipate herself from any form of control and conditioning and to experience life in its many declinations.

Through a training trip between Lisbon, Alexandria in Egypt and Paris, Bella lives grotesque experiences animated by a boundless curiosity, discovers sex, prostitutes herself, dances as if no one is watching her, closes relationships and opens others, is interested in politics, art and culture, yields to the call of worldliness.

Much has been written about this film, about its meaning, about its ability to convey an image of a free and independent woman finally free from any patriarchal legacy. However, there was no shortage of criticism, many of which came from the female world itself which considers the narrative of such a strong and wild creature to be tainted by a purely male point of view which transforms the protagonist into a mere object of desire.

In reality, there is another point of view – less debated than the more immediate one relating to gender identity but equally powerful and enlightening – which deserves to be explored in depth and concerns the value of diversity embodied by the splendid and indomitable Bella Baxter.

The merit of the film is to raise many questions about the human condition and, in particular, about the various forms of expression of the diversity of mankind.

Using the conceptual and classificatory tools of medical and legal science, Bella Baxter could be considered a person with intellectual disabilities, precisely because of that asynchrony between body and brain which produces, at least in the initial phase of her rebirth, significant limitations.

Yet – and this is the strong and revolutionary message of the film – Bella Baxter, despite her limitations and her fragility, is a splendid thinking and feeling being with desires and aspirations, who gives us a different and more enlightened way of conceiving disability. A human condition – like many others – to which no feeling of commiseration or pietism should be connected. Therefore, not an illness, nor a misfortune.

Bella’s way of being and living generates a form of love in the viewer that transcends the need to label her, to catalog her. Bella likes her because she lives as she wants, because she is free to explore, experiment, know, act.

Can we say that this vision of the different or the disabled is rooted in our society, in our culture, in our national and international normative production?

Unfortunately, there is still a long way to go, but there are encouraging signs.

A paternalistic logic of mere protection prevails, especially on a regulatory level, which is offered by a superior subject in favor of a subordinate subject. In other words, we are still tied to a medical-individualist conception, based on the culture of ableism and deficit, which considers diversity and, in particular, disability as an individual problem to be eliminated or mitigated. As a condition of deficit which, depriving the subject of the possibility of living significant experiences, could never be rationally chosen or be a source of pride or identity claim.

In recent years, however, thanks also to the debate stimulated by Disability Studies and the achievements achieved by the Disability Rights Movement, there has been a subversion of the medical-individualist paradigm which has led to the emergence of a new way of conceiving disability, characterized by a critical approach towards the deficit model which defines behaviors only in terms of lack and normality.

Among these new paradigms, the social model of disability deserves to be mentioned, which has radically changed the point of view regarding the disabled person, identifying the solution to the problems linked to disability in the removal of barriers – environmental or deriving from the attitude of others – which prevent disabled person the full enjoyment of their rights and equal opportunities.

From a medical vision (the disabled person is sick and must be treated) we move to a vision focused on the individual-environment relationship, on the context in which the person acts and on the social, economic or behavioral obstacles that lead to the exclusion of those who are different.

The social model has not yet established itself in a systemic manner in legal experience, which still appears conditioned by conceptual and classificatory categories specific to medical science. However, its influence on the birth of a critical theory of law that opposes the anthropological model based on ableism cannot be denied.

In this regard, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), signed in New York in 2006, constitutes the most complete expression, on a regulatory level, of thinking oriented towards the model of social disability, linking the concept of disability to that of protection of human rights and encouraging the affirmation of key topics, such as awareness of one’s rights, non-discrimination, equal opportunities, inclusion and participation, destined to strongly influence legal practice.

The UN Convention has contributed to the spread of a new legal sensitivity, which conceives disabled people as subjects of law who must have equal opportunities to realize their talents and their rights.

It promotes awareness of the condition of the disabled person and their abilities, contributing on an educational level to the diffusion of a new culture of respect for the rights and dignity of the disabled person (art.8).

It encourages active participation, accessibility in all its aspects from an architectural point of view, accessibility of information, training of professionals on the issue, etc. (art.9). It draws the attention of States to the importance of universal design (of products and services that can be used by all people) and personal mobility with the greatest possible independence (art.20).

The Convention has certainly contributed to forging a new way of creating and interpreting the law, which must not be complicit in a process of exclusion and marginalization of the disabled person but have a proactive role aimed at contributing to improving their quality of life.

The hope is that its principles provide the interpreter and operator of the law with a broader understanding of the phenomenon of disability, positively influencing legal experience (understood in its theoretical aspects and practical profiles).

But let’s go back to the initial question regarding the obstacles that Bella Baxter would encounter in today’s society.

One could respond that she would have to face a myriad of cultural barriers even before material ones, that she would not be immune from the widespread tendency towards classification and cataloging which could limit and condition her choices.

All true, but perhaps today she could be just as free to live and experiment. Because she is finally changing the perception of all of us, tired of having to be and appear perfect, of having to fit into the norm.

Deep down we all want to be like Bella Baxter, to experience her freedom which cannot be imprisoned in a definition and which cannot (and must not) scare us.